“Your arrogance offends me. For that, the price just went up ten percent.”

-Bryan Mills

The recent assassination attempt on presidential candidate Donald Trump reflected not just the desperation of liberals and progressives, but a pivotal turning point in the battle of the sexes. Over the past forty years, a surge of educated women has brought us political movements (#Metoo, Black Lives Matter, among others), business owners, professionals, talkative public figures, and, perhaps most effective of all, name-changes. Equality has become Equity, Desegregation has become Inclusion- all under the utopia called Diversity, a policy that almost got the forty-fifth President killed. Images of badly trained, unfit, diminutive female Secret Service Agents, headed by a shamelessly incompetent woman, has exposed sexual politics as a lopsided game of thrones. But as a discourse on the real complementarity between the sexes, the movie Taken is a sort of modern day Rape of Lucretia.

Debuting eight years before Trump’s first term, Taken not only morphed into a three film franchise, but a television series, as well. Despite the spread of DEI in the universities and the workplace, this routine thriller about a father who saves his daughter from sex-traffickers hit a deeper note. Yet the New York Times magazine didn’t treat this phenomenon with the same reverence it accorded Get Out, which, it claimed, “redefined the way we talk about race.” But what film redefines the way we talk about sex? Thelma & Louise? The Color Purple? Barbie? Any serious selection would have to dissect the conceits of our day, and at the top of that list is the construction of the manly woman. To my knowledge, only Taken has turned this conceit on its head.

Soft Power In Focus

The story begins in childhood, where the first bricks of this conceit are laid. As the five year old Kim blows out birthday candles and brandishes her new toy horse, only her mother’s model face completes the frame. No sign of a father or any man. We know from the arresting trailer that something terrible will happen, but we can’t know then that it will involve an alienated father, traded in for a richer husband. From the moment Liam Neeson’s Bryan appears, Famke Janssen’s Lenore wails into him. He was never around, she reminds him, too busy “ruining his life” by serving his country. Apparently, never knowing whether he would return in one piece frayed her nerves more than his. As for quality time with his daughter, isn’t a rich corporate titan at least as busy as a Special Ops titan? In short, ‘Lenny’ is a cliche of an unsympathetic bitch, an image not unknown to #Metoo, or those on a line at Starbucks.

The family story heats up when the single Bryan shows up alone at his daughter’s lavish seventeenth birthday party, gift in hand.. A stranger to both his daughter and her milieu, we feel the sting when the arrival of a real horse trumps his karaoke machine. But as Kim runs ecstatic toward Stuart’s gift, playing one father against another, we also feel the impending irony that she too will become someone’s gift. With her mother’s help, Kim is learning to read men economically just as the remainder of the picture shows what happens when men read women the same way. Trapped in a tug of war not of her making, Kim can only squander our sympathy, for neither Bryan nor Lenore can muster a vocabulary to refine the pampered girl. Sheltered from the horrors of life, Lenore’s global feminism finds Bryan’s warrior ethos too cumbersome. Her contempt for his trade is both personal (bad marriage, absent father) and societal (misguided patriarchy). Up to this point, she shows not the slightest appreciation for the ”particular set of skills” that will eventually save their daughter.

Another irony: our aggrieved feminists come off here like the Roman patriarchy Lucretia’s suicide would ultimately confront. Lenny is the queen of a global, corporate dynasty that includes Bryan’s frenemy, Jean-Claude, the French Deputy Director of Internal Security. Charged with protecting the state, he must also protect Lenny’s illusions, which include ‘security’ for spoiled, naive girls traveling alone internationally.. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. When the retired warrior tries to get to know his daughter, he can’t even tell her what we, the audience, have seen: his saving the life of the pop star Sheera, and the meeting he subsequently set-up between the star and Kim, an aspiring singer. Instead, mother and daughter ambush him with news of the Paris trip. When Bryan resists, knowing he’s got a greater pearl in his pocket, Kim retreats in tears, not wanting to hear anything he has to say. Cue in Lenore’s classic eye roll. “If you don’t (spoil her), I promise you’ll lose her.”

When Bryan finally caves in, the women don’t reward him; they manipulate him further with a series of deceptions. Only when he discovers Kim’s itinerary, for instance, does he learn that she and the nineteen old Amanda will be following the U2 tour throughout Europe. “All the kids are doing it”, says Lenore. By now, Bryan’s in too deep to cancel the whole thing. But he has every right to be furious with his ex-wife for emotionally blackmailing him. “She doesn’t know how the world is”, he argues. “And thanks to you, she never will,” Lenore shoots back, as if one learns to swim with a platinum card for a life-jacket. Not surprisingly, when Kim lands in Paris, she forgets to call her father on the special cellphone he’d given her. So far, so cliche. But here is where the film, like nature itself, begins to punish the lies in direct proportion to their weight. In fact, before the girls even get inside an airport taxi, they’re trapped in the web that will claim one of their lives.

And true to dramatic tradition, the careless one, in this case the wide-eyed Amanda, is the first taken. An acolyte of the sexual revolution, she not only agrees to share a taxi with a male stranger, she reveals to both Kim and Peter that her cousins are out of town, and that they will be alone. It’s fitting that Kim sees Amanda taken just as she confesses her friend’s deception to her father. In a Matrix-like moment, the girls become someone’s prey in an instant. But whereas Morpheus’ directives leave us clueless to Neo’s fate, Bryan’s phone instructions give Kim’s abduction a semblance of structure. When her unseen captor ends the call with his famous “good luck”, he paves the way for us to identify him later. Neo’s redemption begins with a red pill; but here both father and daughter swallow freedom’s red pill, and when the Albanians drag Kim off to Female Hell, Lenore again can only wait for a call that may never come.

What happens next may be anathema to feminist dogma, but Western culture still relies on the “out of touch” Bryans to protect its high-tech Victorian fortress. The new feminine warrior may be game, but she receives his training and employs his machines. Yes, technique can be transferred, but not physical strength. Perhaps this is why Bryan insists that Lenny hear the bad news directly from his colleague: they have ninety-six hours to find Kim, or they’ll lose her forever. When Lenore’s scream is dovetailed by the replay of Kim’s last scream, we witness something Nike, ESPN and seemingly every cop show don’t want us to see- a modern woman’s old-fashioned surrender. Moreover, what provokes it is not her morality, but circumstances caused by her own complacency. Like Lucretia’s rape, Kim’s abduction exposes the corruption of the prevailing order; but whereas the former compelled manly honor to defend a woman’s modesty, the latter compels Bryan to defend feminist promiscuity. With Amanda as the new standard, Kim’s modesty no longer matters.

Men Divided

Like The Rape, Bryan’s struggle will be against men- from vicious immigrants (the street) to Jean-Claude, who “sits behind a desk”. The jagged communication between the two friends stems from the jagged communication between Bryan and the women in his life. “You forget who you’re talking to,” Jean-Claude snaps at his former colleague. “I thought I was talking to a friend,” Bryan shoots back. “You are, as long as you don’t go around tearing up Paris.” This sense of men drifting apart is really what drives the film. At first, the two spotters at the airport, one black and the other French Algerian, confirm ‘the street’s’ more efficient multiculturalism. But on our second visit to Charles de Gaulle, we witness what Bryan sees: the black elder nodding gruffly at his cohort as Ingrid, the fresh Blonde meat, struts through the arrival terminal. Oddly, Peter, so convincing as the engager a day earlier, sighs reluctantly at his new assignment, as if the whole thing disturbed him. This is another reason why we’re pleased when Bryan sweeps in, disrupting the prevailing order.

Tellingly, Peter doesn’t defend his partner and is stumbling halfway up the exit ramp by the time Bryan catches sight of him. This will be the only division we’ll see amongst the sex traffickers; after this, everyone is willing to die for the cause. But because ‘the desk set’ can’t match this zeal, we require freelance fascists to burst the complacency bubble- Dirty Harry, Paul Kersey and John Rambo. But because this fascism is temporary, it can’t confront ‘the desk’ sensibility at its core- the family. In Taken’s whole first act, women had it their way until they blundered into men not willing to play by their rules. This is why writers like Claire Berlinski begged for reason from the #MeToo crowd. Bryan’s not the fanatic, for throughout history his vision has made all other values possible. Peter’s ugly death not only reflects the ugliness of Lenore’s free-market individualism, it sends Bryan to face the ugliness of his friend.

Being a French-American production, Taken’s unsparing portrayal of Jean-Claude may be yet another cliche of a complacent bureaucrat. But the fact that it took an American to cut through the French red tape reveals Luc Besson’s (and perhaps Europe’s) contempt for the plight of European statecraft. When Bryan informs Jean-Claude of his missing daughter, he’s facing more than a bureaucratic obstacle; he’s confronting the fault-line of Western culture, where domestic morality undercuts the charity that makes justice possible. The fact that they talk unobtrusively in plain sight doesn’t explain Jean-Claude’s coldness. The fact that he too is a father doesn’t move him as much as their difference in rank. That’s because Jean-Claude’s domesticity, like Lenore’s, enables him to ignore the (transAtlantic) “mess” he has made of women and freedom. “Every dad dreams about being Bryan Mills,” Luc Besson once said, “and every daughter dreams about having Bryan Mills as a dad.” If so, then why do the fathers and daughters put Mills through such a test?

When Bryan retreats in preparation for his next push, Jean-Claude briefly takes over the narrative, revealing their difference in both talent and commitment. Though outnumbered in a foreign land, Bryan’s off-camera movements still confuse the French agent tailing him. “He’s quiet for now”, Jean-Claude reminds us, after playing with his much younger children. “Soon he’ll be on the move.” When Bryan reappears at night, armed with a clueless translator, he shows a hawkish flexibility forgotten by the blandly consistent doves. Like the street prostitute he uses as bait, he’s easily roughed up and robbed by her Albanian pimp. But his passive aggression enables him to plant the bug that will lead him to the “fresh meat” shipment at a construction site. Jean-Claude, on the other hand, has forgotten the uses of aggression and doubled his burdens- “at first, there were ten or twelve (Albanian traffickers), now there are hundreds of them- and dangerous.” No wonder Bryan leaves for the construction site with an English-Albanian dictionary.

Besson exploits parental fear and loathing even further when he has Bryan waiting on a line that might assign his own daughter as his trick. Lenore’s lessons about the world omit the consideration of such places, leading us to wonder why Bryan would marry her in the first place. Partly, it stems from male sentimentality grown stale, the desire to protect something beautiful (whether a woman or the Eiffel Tower) from the ugliness he knows all too well. But as Bryan enters this sexual bodega, we’re forced to confront our illusions about ‘soft power’. Can an all-female force regularly vanquish these heavily fortified sexual supermarkets? Until this happens, the West need not indulge the social engineers who have mushed ‘gender’ into a gruel for global consumption. “‘All men are created equal’ doesn’t amount to a hill of beans if you don’t make it stick,” counters the retired Secret Service Agent to his pacifist daughter in Suddenly (1954). Fifty-five years later, Taken forces us to reconsider whether making equality ‘stick’ is worth the effort. But when Bryan spots Kim’s denim jacket and lifts the chin of its new owner, the drugged-out zombie gets a second chance, as do Kim and equality.

The construction site scene also triggers the permanent division between Bryan and Jean-Claude, exhibited by the former’s brilliant manipulation of their ‘meeting’ the next morning. The division between “the desk” and “the street”, under the metaphor of construction, leaves Bryan three steps ahead of the French Intelligence. Not only does he not show up for the park bench meeting, he’s not even where he planted the ‘phone kit’ he knows they will trace. More like Lenore than Bryan, Jean-Claude’s casual lifting of the plane ticket, naming Bryan’s flight number and departure time, mirrors Kim’s deceptive itinerary. “C’mon, Bryan, my boss wanted you in chains. This is the best I could do.” The fact that Jean-Claude can’t see Bryan, while the latter “can see him just fine,” mirrors the manly division we’ve seen throughout the ages between artists and philistines, visionaries and bureaucrats. Like life itself, their stalemate is both depressing and reassuring. Bryan can’t inform Jean-Claude of the progress he’s made, but his escape enables the rescued prostitute to place him on his daughter’s trail.

Honor Versus Privilege

Part of the brilliance of Taken lies in its understated treatment of the Jean-Claude/Lenore connection. The fact that the two never meet drives home how pervasive their domestic morality has become. Both are smug to Bryan because they are soft. But the cruel irony is that Lenore’s coddling of Kim leads to Jean-Claude’s indifference to her. “My salary is X and my expenses are Y. As long as I provide for my family, I don’t care where the difference comes from,” Jean-Claude proclaims. The key word here is “provide”, which Jean-Claude, his wife, Lenore and Stuart have redefined to mean ‘pamper’. The elite appropriation of working-class sentiment is just as cynical as the Albanians’ exploitation of Western freedom. And it is only Bryan who confronts both- in California and in Paris. In one of the movie’s most crucial sequences, guns and badges don’t gain Bryan entry into the first place we know his daughter has been (and still might be). Jean-Claude’s business card does.

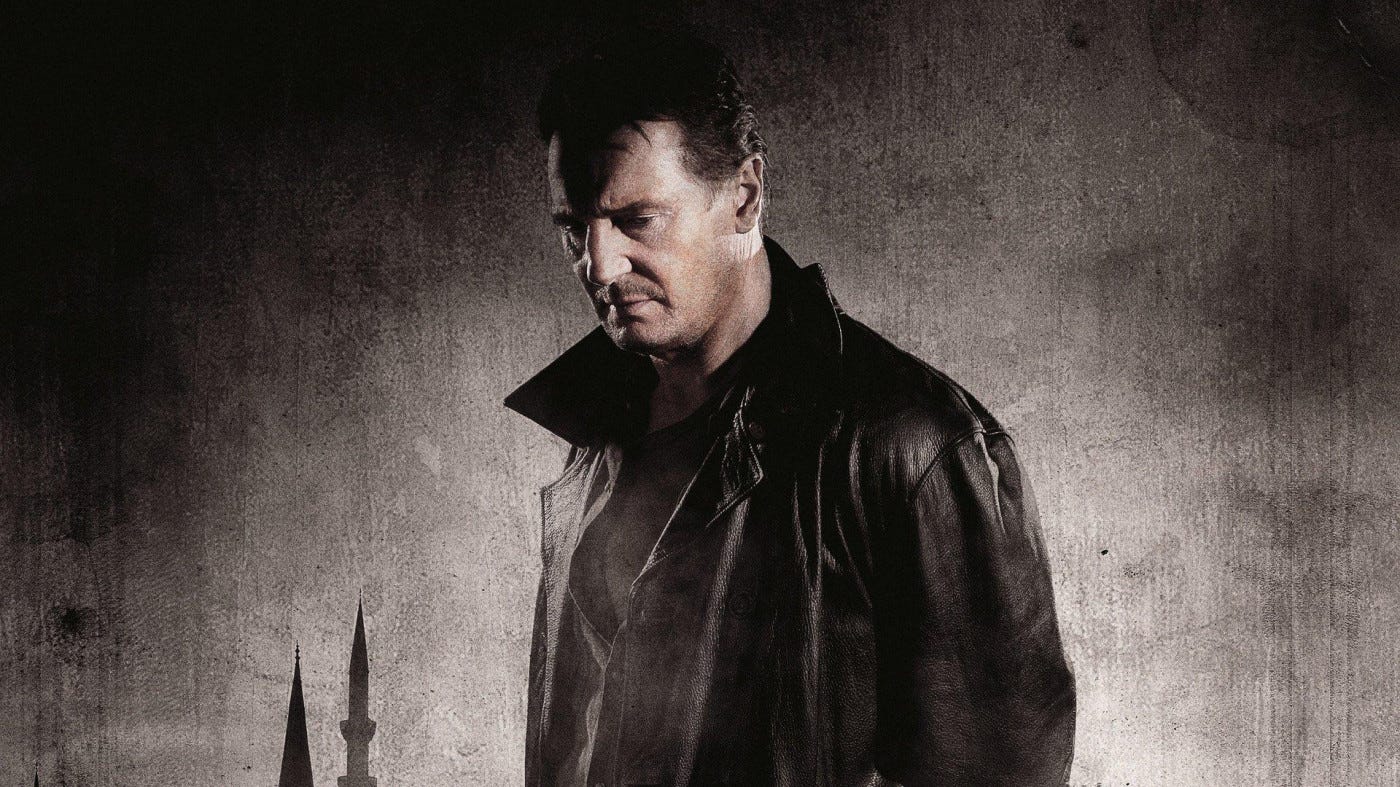

Some will say that Liam Neeson’s age (fifty-six at the time) made his fight scenes as believable as those featuring girls with celery-stalk arms. They would justify this by the micro-quick cutting, which has taken most on-screen fighting out of its spatial context. ‘We can make anyone we want win’, say the new effete directors. But here is what the girls don’t have- Neeson’s presence and reputation as a man’s man. Add to this Bryan’s life-long preparation and his take on Israeli Krav Maga becomes quite okay. The cutting here actually works to the 6’4” Neeson’s advantage: crisp, efficient and real-world. But what makes this fight scene so satisfying is the conversation before it.

At first, Bryan is “the desk” and he’s there for the “renegotiation”. Moving around the room of six top Albanian traffickers, Bryan has all the presumption of a first world power: “Do you know how much it costs to adjust the lens of a satellite orbiting two hundred miles above the earth? Well, our costs go up, your costs go up. It’s only logical.” Though he has their attention, he still gets resistance. “Are you making extortion on us because we’re immigrants?”, says the man who brought him in. “No, I’m extorting you because you’re breaking the law… You come to this country and just because we’re tolerant, you think we’re weak and helpless. Your arrogance offends me..” The worldwide gross of this film suggests that more than scared parents were pumping their fists.

When Bryan pockets the money, standing over the only man who has not spoken, he has set-up one of the best ‘oh, by the way’ moments I’ve seen in fifty years. He hands the quiet, calculating Marko a sheet of paper, scrawled with something a colleague would’ve written as a joke, but which was provided by the dictionary he had gotten from the tutor. When Marko reads “Good luck”, with all the complacency it was meant to evoke, the ensuing fight, pitting the aggrieved father against his daughter’s abductor, fulfills the manly man’s ultimate mission. But the brilliant ‘gotcha’ moment also presents its complications. No, his daughter is not there, but Amanda is- dead and chained to a bedpost. This is why the ‘peace and love’ of pop music (from the Sheera concert to the U2 tour) can’t link the Albanian corruption with the Lenore/Kim/Amanda deceptions. The Sixties abhorrence of war, refined today by a fiction called ‘international law’, is merely part of a larger anthem serenading Jean-Claude’s ‘desk’ and Lenore’s mansion. Bryan wasn’t making a mess of Paris, Paris had already made a mess of itself.

Call this a modern version of chivalry, where the name Patrick Sinclair, the last piece of this sordid puzzle, takes Bryan to (of all places) Jean-Claude’s family dinner table. Having eluded French Intelligence throughout his quest, Bryan has already charmed Jean-Claude’s wife by the time the bureaucrat arrives. Like Marko, he is outmaneuvered in his own home, and Jean-Claude’s displeasure knows that Bryan is completing two circles: the scarlet one that began with his daughter; and the black one that began with the Frenchman’s assertion of ‘desk’ authority. If ‘the street’ gets too much credit today, it’s because the mania for security has so debased honor that we can only spot it in barbaric genius. Of course, Isabelle, Jean-Claude’s wife prefers it this way: “Home for dinner every night, get to see the kids more”. When Bryan shoots her in the arm, his brutality finally matches their own; but despite his best efforts to protect women, the most pampered ones still get it where it hurts.

The Patrick Sinclair ‘party’ is even more damning, a typical multiracial high-society slumfest where Bryan gains entry with fake credentials. As he moves amid the mechanical thump of house music, we see an entire metaphor of sex-trafficking. Out front, an oblivious designer dress crowd that might easily include Lenore; and downstairs, the ‘best’ kidnapped girls auctioned off to anonymous billionaires sipping champagne in black, glassed-in suites. Here, women reading men economically in Act One has only intensified the male version in Act Three. This is why Bryan’s superb improvisation throughout now fails; he’s penetrated the corrupt male’s inner sanctum. As he pours champagne for an Arab buyer even prettier than Kim, how will he get her out? That’s when we finally see her, dazed, bewildered, up for sale. In another bitter twist, Bryan drives up his daughter’s price just for the opportunity to save her.

When he’s captured for the first time in the movie, Sinclair, a father of three, seems more sympathetic to Bryan’s plight than the Deputy Director of Security. But when the bound captive pleads to buy his own daughter, Sinclair’s ethos mirrors Jean-Claude’s: “In this business, there are no returns, no refunds, no discounts and no buy-backs…” What makes Bryan’s escape plausible is that his surprise appearance hastened his captors into an error. When Sinclair utters in his prep school English, “Kill him quietly, I have guests,” Bryan’s vicious take-down of the ringmaster dishes out to the guests the bloodied corpse they deserved to see.

All of which brings us back to the attempted assassination of Trump, for the very operations for which Bryan sacrificed his life, and which brought down an international sex-trafficking ring, has brought forth a new Jean-Claude-Lenore-Albanian connection (The FBI, the DOJ, and Homeland Security). The moral question is not whether Trump is evil, but whether a second-hand moral code like DEI can acknowledge its own evil. But that won’t happen when even an honest movie like Taken fails its own test of chivalry. Indeed, Kim deserves something grand for her suffering, and when Bryan presents her to the pop star Sheera, we complete the scarlet circle between father and daughter.

But is pop culture the just end to Bryan’s sacrifice? For all his heroism, Bryan’s just another twenty-first century father, divorced, disconnected from his child, and made over by his woman into a rival of “her desk”. Yes, Bryan reunites with Lenore in Taken II; and Kim repays her father by saving her parents when they are taken. But does Bryan’s sacrifice (or Kim’s captivity) drive feminism to transcend mere self-interest? The horrendous performance of the Secret Service in protecting Trump, the finger-pointing, the delayed and deceptive explanations all point to Soft Power’s crisis of Responsibility. What Taken shows is that machine-life has paved the way for a new Dark Age, one in which the Bryans of the West will have to reclaim their legacy.